"Correlation is Not Causation": A Gentle Intro to Causal Inference

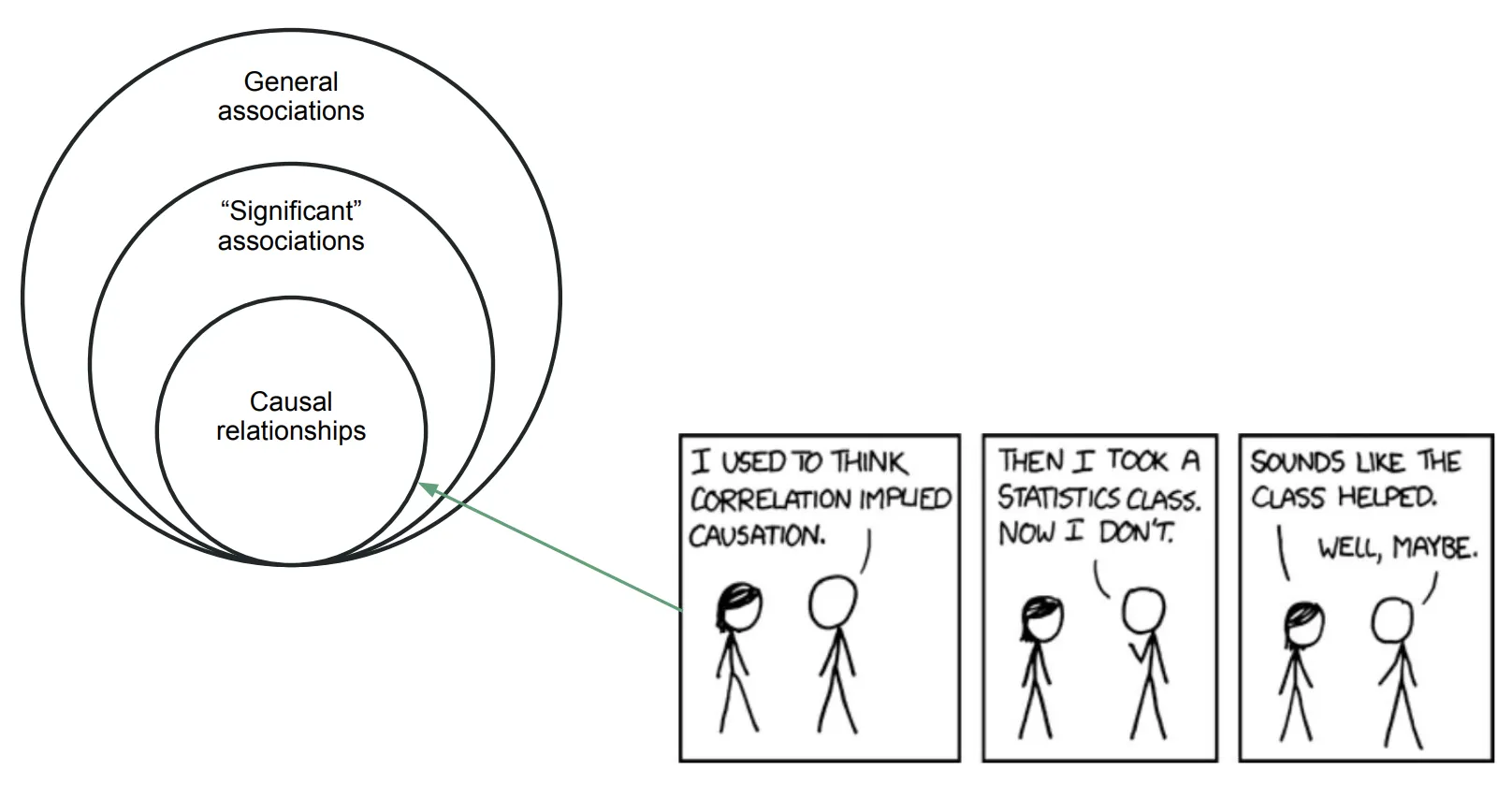

As data professionals, we're taught from day one to chant the mantra: "Correlation is not causation." We see that ice cream sales and shark attacks are correlated, but we know one doesn't cause the other (the hidden cause, or confounder, is summer weather). This is a great starting point, but it's not the end of the story. Simply stopping at "correlation is not causation" is like learning to identify problems without ever learning how to solve them.

The real question isn't "Are these two things correlated?" but rather, "Did my action cause this outcome?" Answering this is the domain of causal inference, and it's what separates a data analyst from a trusted advisor.

The Fundamental Problem: We Can't Clone Our Customers

Imagine a user signs up for your product. You show them a new onboarding tutorial. A week later, they become a paying customer. Did the tutorial cause them to convert?

The only way to know for sure would be to travel back in time, not show them the tutorial, and see if they still converted. This impossible, "what if" scenario is what researchers call the counterfactual. The core challenge of causal inference is that we can only ever observe one reality. We can't clone our customers to see what they would have done differently.

So, how do we solve this? We use clever statistical methods to simulate a counterfactual world.

The Gold Standard: Randomized Controlled Trials (A/B Testing)

The cleanest way to establish causality is to run a Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT), which you already know by its industry name: the A/B test.

Why is randomization so powerful? When we randomly assign users to a control group (Group A, no tutorial) and a treatment group (Group B, new tutorial), we can be reasonably sure that, on average, the two groups are identical in every way except for seeing the tutorial. Randomization balances confounders across groups, especially with large samples, so any systematic difference in outcomes can be attributed to the treatment rather than other factors.

If we then observe a statistically significant difference in conversion rates, we can reasonably infer that the tutorial caused the change. We have strong evidence that we’ve isolated the effect of our intervention.

When A/B Tests Aren’t Possible: The World of Observational Causal Inference

But what if you can't run an A/B test? Maybe the feature is already live for everyone, or it's unethical or impractical to withhold it. This is where most data lives, and it's where more advanced techniques come into play.

These methods aim to statistically mimic an RCT using historical, observational data. Here’s the intuition behind one popular method:

Propensity Score Matching: Imagine we want to know the effect of a "pro" subscription on user engagement. We can't force people to not be "pro." So instead, we look at our data and, for every "pro" user, we try to find a "free" user who looked almost identical to them right before they subscribed—similar activity levels, similar location, similar sign-up date, etc. We calculate a "propensity score" (the probability of subscribing) for each user and match them up. By creating these carefully matched pairs, we build an artificial control group, allowing us to estimate the causal effect of the subscription.

Of course, this approach can only balance factors we can observe and measure. Unobserved differences—like motivation or intent—can still bias results, so causal claims from observational data always require careful interpretation.

Other methods include Difference-in-Differences, Instrumental Variables, and Regression Discontinuity, each with its own clever way of trying to isolate a causal effect from messy, real-world data. Behind these approaches lies a powerful framework called causal diagrams (or DAGs), which help visualize and reason about assumptions — a great next step for anyone wanting to go deeper.

Why This Matters for Your Career

Moving from correlation to causation is the leap from making reports to driving strategy.

A correlational insight sounds like: “We noticed that users who use Feature X have lower churn.” (Interesting, but what do we do?)

A causal insight sounds like: “Our analysis shows that encouraging new users to adopt Feature X would cause about a 5% reduction in churn, generating an estimated $200k in revenue.” (This is a clear, actionable business case.)

Understanding causal inference allows you to move beyond simply describing "what is" and start advising on "what we should do." It's about providing the confidence the business needs to invest in one feature over another, and it’s one of the most valuable skills a data professional can develop.