A Gentle Intro to Main Data Storage and Processing Concepts

I still remember sitting in my very first Big Data lecture, scribbling notes as my professor declared, “Big Data is all about volume, velocity, and variety… you’ll get it later.” It sounded both grand and maddeningly vague. 🤔 Driven by confusion, I dove head-first into practical tools—Spark, Kafka, Hive—and soon realized there was a core set of concepts everyone in data needs to master. Along the way, terms like “data lake,” “lakehouse,” “Delta Lake,” and “data warehouse” all blurred together in my head.

This article aims to demystify these storage architectures and ingestion patterns for starters—so you can spend less time Googling and more time building. We’ll sprinkle in real-world examples to show why you might pick one approach over another.

Storage Architectures & Formats

Anecdote: At first I was totally lost on the difference between a lakehouse and a warehouse. Then I realized they solve different problems—like choosing between a Ferrari and a pickup truck.

1. Data Warehouse

A data warehouse is a rigid, schema-on-write system optimized for SQL analytics and BI. You define tables up front, load transformed data, and enjoy rock-solid performance on reporting queries. Think Snowflake, Redshift, or BigQuery.

- Pros: Fast, consistent query speeds; mature tooling for dashboards.

- Cons: Higher compute costs; tricky with semi-structured or unstructured data.

Example: A bank collects millions of daily transactions. They store customer accounts, balances, and transaction history in well-defined tables. Every night an ETL job cleans and aggregates that data so fraud teams and auditors can run quick, reliable SQL reports.

2. Data Lake

A data lake is a low-cost, schema-on-read repository (often on S3, ADLS, or GCS) that stores raw data in any format—CSV, JSON, logs, images, you name it. Great for ML experiments, but without governance it can become a “data swamp.”

- Pros: Ultra-flexible; stores everything as-is.

- Cons: Can get messy; discovery and cleanup are your responsibility.

Example: An e-commerce startup dumps clickstream logs, user profiles, and raw server metrics into an S3 bucket. Data scientists then spin up Spark or Athena queries against that raw data—no predefined schema required—when exploring new ML features.

3. Data Lakehouse

A lakehouse combines the openness of a lake with the performance and management features of a warehouse. You get ACID transactions, metadata management, and time travel on top of object storage. Examples include Delta Lake and Apache Iceberg.

- Pros: Single platform for BI and ML; lower storage costs than pure warehouses.

- Cons: Newer pattern; ecosystem still evolving.

Example: A media company uses Delta Lake on S3. Their analytics team runs BI dashboards on the same data ML engineers use for training recommendation models—no separate copies, and they can rollback to a previous snapshot if something breaks.

4. Delta Lake

Delta Lake isn’t a location but a table format built on Parquet that adds a transaction log for ACID guarantees, schema enforcement, and time travel.

- Pros: Safe concurrent writes, rollbacks, incremental pipelines.

- Cons: Requires engines that speak the Delta protocol (e.g., Databricks).

Example: When ingesting IoT sensor data in real time, Delta Lake lets you append new Parquet files while running batch analytics—without worrying about partial writes or inconsistent reads.

File Formats vs. Table Formats

File Formats (Parquet, ORC, Avro) define on-disk encoding:

- Parquet (columnar) excels at compression and column pruning.

- ORC brings similar strengths in Hive/Spark ecosystems.

Table Formats (Delta Lake, Iceberg, Hudi) sit above files, managing collections with metadata layers:

- Enable safe commits, rollbacks, and schema evolution.

- Make your lake behave more like a warehouse under the hood.

Why It Matters: If you simply dump Parquet files to S3, you’ll struggle to perform reliable updates or deletes later. A table format gives you those database-like guarantees without leaving object storage.

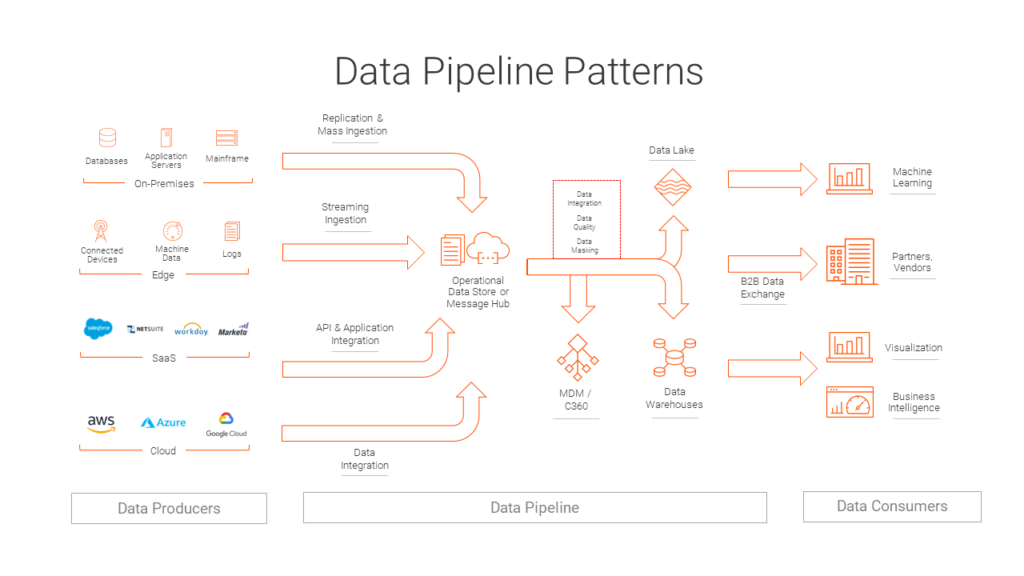

Ingestion Patterns

Important: While this is not exhaustive, it provides a simple starting point to understand the main and most common ingestion patterns, ELT and ETL!

ETL vs. ELT

ETL (Extract → Transform → Load):

- Extract raw data from sources.

- Transform it on a dedicated engine (e.g., Spark).

- Load the cleansed results into the warehouse.

ELT (Extract → Load → Transform):

- Extract data from sources.

- Load it directly into the destination (e.g., Snowflake).

- Transform in-place using the warehouse’s compute.

Example – ETL: A retail chain pulls POS data, transforms it (currency conversions, day-of-week aggregations) in Spark, then loads a clean star schema into Redshift for nightly reporting.

Example – ELT: A SaaS company loads raw event streams into BigQuery, then uses SQL (and dbt) to transform for analytics—letting them re-transform historical data anytime without rerunning a heavy Spark job.

Batch Processing vs. Stream Processing

| Aspect | Batch Processing | Stream Processing |

|---|---|---|

| Latency | Minutes–hours (scheduled jobs) | Milliseconds–seconds (real time) |

| Volume | Large, finite sets | Unbounded, continuous |

| Complexity | Simpler pipelines | State management, windowing, exactly-once |

| Use Cases | Nightly reports, ETL, backups | Real-time dashboards, fraud detection, IoT |

Batch shines when throughput and cost efficiency matter. Stream wins for freshness and immediate reaction, but requires platforms like Kafka, Flink, or Spark Structured Streaming.

Hybrid architectures—Lambda (both batch + speed) or Kappa (all-stream)—help teams balance accuracy with real-time needs.

Wrapping Up

From my initial confusion in that lecture to architecting production pipelines, these core concepts—storage architectures (warehouse, lake, lakehouse), file vs. table formats, and ingestion patterns (ETL/ELT, batch/stream)—form the bedrock of every scalable data platform. Whether you’re handling banking transactions or training ML models on terabytes of logs, mastering these pillars will keep your pipelines robust, cost-effective, and, yes, a little less mysterious.

So, next time someone drops “lakehouse” into conversation, you can smile and say, “Ah, yes—let me explain…”