Beyond "git push": Crafting Projects That Anyone Can Run (Including Your Future Self!)

So, you have mastered the Git habits from our last chat ("From Notebook Chaos to Production Calm"). Your code is versioned, you’re branching like a pro, and “if it isn’t on a remote, it doesn’t exist” is practically tattooed on your brain. Awesome! But what happens after the push? How do you make sure your brilliant project isn't just a folder of code, but a living, breathing application that others can actually use without summoning a tech priest?

The Day My README Caused Existential Dread (and a Bash Script Saved the Day... Temporarily)

Picture this: I'd poured my heart into a Streamlit app. It was a prototype, a validation-of-concept for some important stakeholders. "Just try it out!" I said, beaming with pride, and sent them a link to the private GitHub repo. My README was, I thought, pretty decent. It had the git clone command, a note about Python 3.9, a requirements.txt, and the golden streamlit run app.py line. Easy peasy, right?

Wrong. So, so wrong.

The feedback started trickling in, not about the app's features, but with phrases like:

- "What's a 'virtual environment' again?"

- "It says 'pip' not found... do I need to install Python? I thought I had it."

- "I opened the

app.pyfile, but nothing happened." - "This

requirements.txt... do I just read it?"

My heart sank a little. These were smart people, but they weren't necessarily terminal wizards. They just wanted to see the app. My "simple" instructions were a CLI labyrinth. I was asking them to perform a series of arcane incantations just to get to the starting line.

In a moment of panicked inspiration, I whipped up a start_app.sh bash script. It was beautifully basic, aiming to automate the setup:

#!/bin/bash

echo "Setting up your awesome Streamlit app..."

# --- Check for Python 3 ---

if ! command -v python3 &> /dev/null; then

echo "Python 3 could not be found."

echo "Please install Python 3. You can download it from https://www.python.org/downloads/"

echo "Or, on Debian/Ubuntu: sudo apt update && sudo apt install python3 python3-pip python3-venv"

echo "On macOS (using Homebrew): brew install python"

exit 1

fi

echo "Python 3 found."

# --- Check for pip (usually comes with Python 3) ---

if ! python3 -m pip --version &> /dev/null; then

echo "pip for Python 3 could not be found."

echo "Try: sudo apt install python3-pip (Debian/Ubuntu) or ensure your Python installation includes pip."

echo "You might also try: python3 -m ensurepip --upgrade"

exit 1

fi

echo "pip found."

# --- Create a virtual environment if it doesn't exist ---

VENV_DIR="venv"

if [ ! -d "$VENV_DIR" ]; then

echo "Creating virtual environment in '$VENV_DIR'..."

python3 -m venv "$VENV_DIR"

if [ $? -ne 0 ]; then

echo "Failed to create virtual environment. Please check your python3-venv package."

exit 1

fi

fi

echo "Activating virtual environment..."

# Note: Activation is for the current script's session.

# For Windows, you'd need a .bat or .ps1 script with `venv\Scripts\activate`

source "$VENV_DIR/bin/activate"

echo "Installing dependencies from requirements.txt..."

pip install -r requirements.txt

if [ $? -ne 0 ]; then

echo "Failed to install requirements. Make sure requirements.txt exists and is valid."

exit 1

fi

echo "Starting Streamlit app..."

streamlit run app.py

echo "App should be running. Check your browser or open http://localhost:8501"

I told them: "Clone the repo, then just open your terminal in that folder and type ./start_app.sh (or bash start_app.sh on some systems after chmod +x start_app.sh)."

Suddenly, magic! For them, it was one command, a flurry of text they could mostly ignore, and then a browser tab popping open with the app. They were delighted. I was relieved. But a nagging thought remained: this bash script was a band-aid, a clever hack for local demos. What if I needed to deploy this app? What if a new team member joined? Was I going to email them a bash script and hope for the best?

This, my friends, is where we graduate from just versioning code to building robust, reproducible, and welcoming projects. My little bash script was a step towards better "Developer Experience" (DX) for my stakeholders, but true production calm requires more.

Let's explore the habits and tools that bridge this gap.

1. Your Project's Front Door: The Indispensable README.md

My stakeholder saga highlighted a key truth: your README is often the very first interaction someone has with your project. It's not just a note-to-self; it's your project's welcome mat, instruction manual, and sales pitch rolled into one.

While my bash script papered over the cracks, a truly great README aims to:

- Explain the "What" and "Why": A brief, clear description of what the project does and the problem it solves.

- Flawless Setup Instructions:

- Prerequisites (Python version, Node version, specific OS tools if any).

- How to set up the development environment (e.g.,

python3 -m venv venv,source venv/bin/activate). Be explicit! - How to install dependencies (

pip install -r requirements.txt,npm install).

- How to Run It:

- For an application:

streamlit run app.py,python main.py,npm start. - For a library: How to import and use core functions.

- For an application:

- How to Run Tests: Essential for contributors and for verifying setup (

pytest,npm test). - (Optional but Good) Project Structure Overview: A brief explanation of key directories if the project is complex.

- (Optional but Great) Contribution Guidelines: If you want others to contribute.

- License Information (Not strictly needed, but a good nice to have!).

Key takeaway:

Write your README as if you're explaining it to a smart colleague who's never seen your project before... or to your future self, six months from now, after you've forgotten all the intricate details.

2. A Place for Everything: Sensible Project Structure (and Cookiecutter to the Rescue!)

Ever opened a project folder and felt like you'd walked into a hoarder's attic? Files everywhere, no rhyme or reason? That's a recipe for confusion.

A well-organized project structure makes it easier to:

- Find what you're looking for.

- Understand the project's components.

- Onboard new developers.

- Scale the project.

Common conventions include:

src/orproject_name/: For your main source code.tests/: For all your tests.docs/: For detailed documentation.utils/: For utility scripts (likeformat_dates.py, but hopefully for more advanced things!).data/: For small, essential data files (remember.gitignoreand DVC/Git LFS for large data from the last article!).notebooks/: For exploratory Jupyter notebooks.

"But setting this up every time is tedious!" I hear you cry. Enter Cookiecutter!

Cookiecutter is a command-line utility that creates projects from project templates. You find a template you like (or make your own), run cookiecutter gh:someuser/some-template, answer a few questions, and poof – a beautifully structured project skeleton appears, often complete with a starter README, .gitignore, license, and even basic CI configuration!

Popular Python Cookiecutters:

cookiecutter-pypackage: For Python packages.cookiecutter-django: For Django projects.cookiecutter-flask: For Flask projects.- Many data science-specific ones too! A quick search for "cookiecutter data science" will yield great results.

Starting with a good structure from day one saves countless headaches.

3. Keeping it Clean and Consistent: Linters, Formatters, and Pre-Commit Hooks

Okay, your project is structured, and your README is welcoming. Now, let's talk about the code itself. In a team (even a team of one, with "Past You" and "Future You"), code consistency is king. It makes code easier to read, understand, and debug.

- Linters (e.g.,

flake8,pylintfor Python): These are static code analysis tools that flag programmatic errors, bugs, stylistic errors, and suspicious constructs. Think of them as an automated code reviewer that catches common mistakes. - Formatters (e.g.,

black,isortfor Python): These tools automatically reformat your code to adhere to a specific style guide. No more debates about where the comma goes – the formatter decides!blackis famously "uncompromising."isortspecifically sorts your imports.

"Great tools," you say, "but I'll forget to run them!" That's where the magic of pre-commit hooks comes in.

pre-commit is a framework for managing and maintaining multi-language pre-commit hooks. You define a small YAML file (.pre-commit-config.yaml) specifying which checks to run (e.g., run black, then flake8, then check for large files). Before Git actually creates a commit, it runs these checks. If any fail, the commit is aborted, giving you a chance to fix things.

Example .pre-commit-config.yaml:

repos:

- repo: https://github.com/pre-commit/pre-commit-hooks

rev: v4.5.0 # Use the latest version

hooks:

- id: trailing-whitespace

- id: end-of-file-fixer

- id: check-yaml

- id: check-added-large-files

- repo: https://github.com/psf/black

rev: 24.2.0 # Use the latest version

hooks:

- id: black

- repo: https://github.com/pycqa/flake8

rev: 7.0.0 # Use the latest version

hooks:

- id: flake8

Install pre-commit (pip install pre-commit), run pre-commit install in your repo, and enjoy automated quality control!

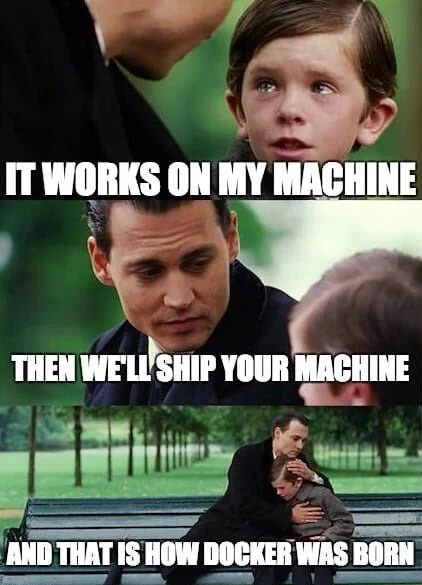

4. The Ultimate Reproducibility: Dockerizing Your App (Goodbye, "Works On My Machine"!)

Remember my stakeholder Streamlit app saga? The bash script was a decent local fix. But the real solution for making that app (and almost any app) truly portable, reproducible, and easy to deploy is Docker.

If you're new to Docker, think of it like this: a Docker container is like a standardized shipping container for your application. It packages up your application code along with all its dependencies (libraries, system tools, runtime, etc.) into a single, isolated unit. This container can then run consistently on any machine that has Docker installed, whether it's your laptop, a colleague's Mac, or a cloud server.

This solves the "it works on my machine" problem once and for all.

How does it work? With a Dockerfile.

A Dockerfile is a text file that contains instructions for building a Docker image (a blueprint for your containers). The official Python base images (like python:3.9-slim) already come with Python and pip pre-installed, so you don't need to install them manually within the Dockerfile itself.

For my Streamlit app, a simple Dockerfile might look like this:

# Use an official Python runtime as a parent image

# This image comes with Python and pip pre-installed.

FROM python:3.9-slim

# Set the working directory in the container

WORKDIR /app

# Copy the requirements file into the container at /app

# This is done first to leverage Docker's layer caching if requirements don't change.

COPY requirements.txt .

# Install any needed packages specified in requirements.txt

# --no-cache-dir reduces image size, --trusted-host pypi.python.org can help in some networks

RUN pip install --no-cache-dir --trusted-host pypi.python.org -r requirements.txt

# Copy the rest of the application code into the container at /app

COPY . .

# Make port 8501 available to the world outside this container (Streamlit's default port)

EXPOSE 8501

# Define environment variables for Streamlit

# Running headless is good for server environments

ENV STREAMLIT_SERVER_PORT=8501

ENV STREAMLIT_SERVER_HEADLESS=true

ENV STREAMLIT_SERVER_ENABLE_XSRF_PROTECTION=false # May be needed depending on setup/proxy

ENV STREAMLIT_SERVER_ENABLE_CORS=false # Adjust as needed for your CORS policy

# Run app.py when the container launches

# Use 0.0.0.0 to make it accessible from outside the container

CMD ["streamlit", "run", "app.py", "--server.port=8501", "--server.address=0.0.0.0"]

With this Dockerfile in my project, anyone could build and run my app with just two Docker commands (after installing Docker, of course!):

docker build -t my-streamlit-app .(Builds the image and tags it asmy-streamlit-app)docker run -p 8501:8501 my-streamlit-app(Runs the container and maps port 8501 from the container to port 8501 on your host machine)

No more fussing with Python versions, virtual environments, or pip commands on the host machine! Stakeholders (or deployment systems) just need Docker.

For more complex applications with multiple services (e.g., a web app and a database), Docker Compose allows you to define and run multi-container Docker applications with a single docker-compose.yml file. But that's a topic for another day!

5. Quick-Start Checklist for Next-Level Repos

| Habit | Tooling Example | Payoff |

|---|---|---|

| Welcoming Entry Point | Comprehensive README.md |

Faster onboarding, clarity for users & future-you, fewer setup questions |

| Organized Foundation | Sensible dir structure, Cookiecutter templates | Easy navigation, scalability, consistency across projects |

| Automated Quality | Linters (Flake8), Formatters (Black), pre-commit |

Fewer bugs, consistent style, improved readability, less review churn |

| True Reproducibility | Dockerfile, Docker |

"Works everywhere," simplified deployment, no dependency hell |

| (Bonus) Dependency Lock | pip freeze > requirements.txt, Poetry etc... |

Pinning exact dependency versions for consistent builds across time and environments |

Final Word: From Code to Craftsmanship

Moving beyond just writing code that "works" into the realm of crafting well-structured, documented, and reproducible projects is a hallmark of a professional developer. These practices aren't about adding bureaucratic overhead; they're about saving yourself (and your team) immense amounts of time, frustration, and late-night debugging sessions.

My bash script solved an immediate problem, but embracing tools like good READMEs, project templating, automated quality checks, and especially Docker, addresses the underlying need for clarity, consistency, and reproducibility. These are the building blocks that lead to true "production calm."

So, next time you start a project, or even look at an existing one, ask yourself: "Is this welcoming? Is it organized? Is it easy for someone else (or future me) to pick up and run, anywhere?"

Your journey to becoming a more effective and less-stressed developer continues! What will you implement first? 🚀